KEYWORDS

Multiple chronic conditions, multimorbidity, patient experience

INTRODUCTION

As the prevalence of multiple chronic conditions (MCC) increases, the coordination of care for patients with MCC becomes more important. In general, ‘multiple chronic conditions’ is defined as the presence of two or more chronic medical conditions in an individual.1 In 2010, the prevalence of patients with MCC in European countries ranged between 32 and 58%.2 The United Nations predicts that the number of people aged 60 years and older will increase by 56% between 2015 and 2030.3 Because the occurrence of MCC is strongly related to rising age,4-6 it is expected that the prevalence of MCC will also increase in the future. Irrevocably, the number of patients with MCC consuming healthcare will supposedly increase over the upcoming years. According to several studies, patients with MCC utilise more healthcare than patients with a single condition; they have more contacts with healthcare providers and have a higher risk of functional impairment or hospitalisation.7-10 As a consequence, current research is increasingly focusing on reforming chronic care delivery for patients with MCC.5,11,12

Research on the optimal management of patients with MCC first started in the primary care setting. Further development of communication and coordination, in order to improve a patient’s involvement and self-management, offered a promising perspective. According to Kenning et al., ‘hassles’ (obstacles that patients perceive when dealing with healthcare situations) might have an influence on a patient’s self-management of MCC and self-reported medication adherence.11 Interestingly, there was a trend towards improved prescribing and medication adherence in the review about current organisational interventions by Smith et al. They suggest that focusing on specific problems experienced by patients with MCC might be an important element of improving outcome.5 Moreover, a recent review by Hasardzhiev et al. identified knowledge and involvement in decision-making, proper communication and coordinated care as important factors influencing patients’ experiences of care and consequently patient outcome.12 Overall, in primary care it seemed that improving a patient’s care experience and organisation might eventually improve their outcome.

Current secondary care primarily focuses on diseases and today’s hospitals are mostly organised around single disciplines.2 However, the care of patients with MCC usually transcends disciplines. Interdisciplinary consultation is common in hospital, but interdisciplinary treatment plans are usually only used for single diseases. To face the increasing number of patients with MCC and their healthcare needs, improving the coordination of care might be necessary in secondary care. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for MCC (2016) recommends considering a patient-centred approach, for example when patients experience problems in managing their treatments, when multiple care providers are involved or when patients take multiple medicines. However, the evidence available for this individual plan is limited, because patients with comorbidity are frequently excluded from trials and outcomes of interest for those groups are not taken into account.13 This raises the question which specific factors influence the quality of (secondary) care for patients with MCC and what is the best way to investigate them.

Inquiring about patients’ care experiences can be used to obtain insights into their perspectives on current secondary care.14 The NICE guideline summarises the research on the barriers experienced by patients and healthcare professionals in obtaining optimal care for patients with MCC. They describe themes such as understanding MCC, accessibility and format of services, communication and patient-specific factors.13 In order to compare and define whether a change in the conventional Dutch secondary care is necessary, we decided to first conduct a qualitative study. The aim was to explore outpatients’ experiences, beliefs and understandings of the current secondary care, because it is indicated that this is important to form new hypotheses.15 What is, in the patient’s opinion, currently affecting their experience of care? Do they experience the secondary care to be diseasespecific and monodisciplinary oriented? After exploring the patient’s experiences, the themes found might be used to offer a new angle for the design or implication of interventions for patients with MCC in the outpatient hospital care.

METHODS

Design

A qualitative, interpretative description design was used15,16 with semi-structured interviews, qualitative content analysis and collection of baseline participant characteristics.

Study population

The study population was recruited from the internal medicine and geriatric outpatient departments of the Gelre Hospitals in Apeldoorn using posters, flyers and direct recruitment by internal medicine physicians and geriatricians during a consultation. The physicians were instructed to recruit patients who met the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: aged 18 years or older, with the ability to communicate in Dutch and/or English and with two or more chronic conditions of which at least two necessitated regular outpatient visits (≥ 2 times a year). Moreover, they had to be treated by at least two specialists in outpatient departments of Gelre Hospitals. Patients with severe cognitive impairment defined by inability to recall diseases and hospital visits were excluded.

Patients who were hospitalised less than four weeks prior to the interview were excluded as well. After recruitment by the physicians or posters/flyers, the executive researcher (MV) performed the final assessment using the inclusion and exclusion criteria and either included or excluded the patients. The research protocol was approved by the regional and local research ethics committee.

Participant characteristics

Five participants were female. The age ranged from 67-92 years, with a median age of 71.5 years. Seven participants were or had been married. Five participants were living alone (including one married couple who were living separately). Moreover, all participants were Dutch and educated at primary school level, four participants received further education (table 1).

Data collection procedure

Interviews

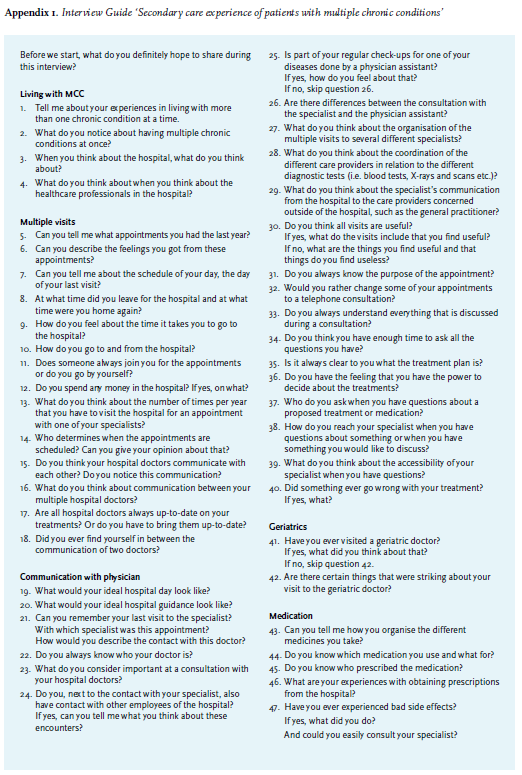

Interviews were carried out in May and June 2017 by the executive researcher. The interviews were conducted at the participant’s home address or at the geriatric outpatient clinic, depending on the participant’s preference. Participants were requested to fill out a written consent form beforehand. The duration of each interview was approximately 1.5 hours. The interviewer used a predesigned interview guide (Appendix 1). All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Medical records

Baseline participant characteristics were collected through interview and from the Electronic Medical Record (gender, age, illnesses, education and work, medication, number of visits in the last year, number of hospitalisations and re-hospitalisations in the last year, current living situation, use of home care or informal care, functional status with Katz-ADL-6 scores and clinical frailty scale (CFS)). For the description of MCC three different measures were used: disease count (according to Barnett et al, 201217),the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS). We decided to use three measures to enhance comparability and chose these three because they are among the most commonly used in primary care and community settings.18 Descriptive statistics were used to give an overview of the population.

Data analysis and data saturation

Interviews were held until data saturation was achieved, which meant that no new insights emerged from the data. A coding structure was developed iteratively. During the coding process Atlas.ti, version 7, was used as a supportive computer program. The executive researcher coded the first transcripts using sensitising concepts and an open coding approach. Using close reading and constant comparisons, new themes and categories were identified. Following open coding, the different categories and themes were connected during the axial coding process. After the axial coding process, one senior researcher assessed the codes and corresponding quotes. Consequently, the executive researcher and senior researchers reached consensus through discussion. The final coding structure was then developed, and core categories and themes were integrated using selective coding. The executive researcher then coded all interviews using the final coding structure.

RESULTS

Interviews

Eight interviews were conducted (table 1). Three internal medicine physicians and two geriatricians recruited seven participants from their outpatient clinic. One participant responded to the flyer/poster.

Three patients (two recruited by one internal medicine physician, one recruited by poster/flyer) were excluded: One of these patients was hospitalised less than 4 weeks prior to the interview, one was not treated by multiple hospital-based physicians in Gelre Apeldoorn and one interview was cancelled because of a participant’s acute illness.

MCC and functional characteristics

Most of the participants were suffering from 7 or 8 conditions. The CCI scores ranged from 3-9; most participants scored 5 or 6 points. The CIRS ranged from 25-38 points, with a median of 29.5 points. The participants were relatively independent in daily life, with KATZ-ADL 6 scores varying from 0 to 2 points and CFS fluctuating between ‘managing well’ (3 points) and ‘moderately frail’ (6 points) (table 1).

Identification of themes

The eight identified themes were divided into two groups (table 2).

Being a patient with MCC in the hospital

The participants described how they had to manage multiple hospital visits and interact with several hospital-based physicians. They sometimes depended on others for support. Eventually, they become experienced patients who know how to plan, what to expect and how to get things done, the participants stated.

a) Living with MCC

Not ill, but more functionally impaired and less independent

Participants reported that they do not realise on a daily basis that they have MCC but try to accept it. Some said that being ill does not or did not keep them from doing what they desire in their lives, such as ‘strolling through the woods’ or ‘accomplishing a successful career’. They did, however, notice the gradual decline of functional status and mobility that is entangled with ageing and having MCC. The loss of independence hangs over their heads every time they experience symptoms, develop a new condition or when their conditions interact. ‘Well, things changed slowly. Previously, when I had to visit the hospital, I would drive there myself. Now I am not able to do that anymore. Other than that, nothing has changed.’ (P2)

Ambivalent coping with MCC

Living with MCC required coping and participants described how they experience feelings of acceptance and self-distancing, but also of insecurity, frustration and guilt. On the one hand, some described that they ‘do not (want to) dwell on being ill’ and ‘(try to) just put up with it’. On the other hand, others reported feeling insecure and sometimes frustrated when the diagnosis or the future was uncertain. Some participants portrayed how they experience adapting to a new situation every time: sometimes they are ‘hoping it will get better’ and ‘trusting’ that they can ‘manage on their own’. At other times, they must ‘give in’ and, sometimes reluctantly, acknowledge they need help or care equipment such as a wheeled walker.

The complexity of handling medication

The number of medicines per participant ranged between 13 and 17, with one outlier with only four medicines. Six participants managed their own medications, three of these participants used a compliance device (baxterrol). Two participants (one also had a compliance device) said ‘I rely on my partner’. Three participants reported that they know for every medicine why they take them, others ‘roughly know’ or ‘had no idea’.

‘Well, the brown one is for and there are medicines I have been taking for years, that one is for, well, I do not know right now. I trust it is…’ (P5)

Two of them trusted that the doctors could see all the medication in the computer; others always brought the medication compliance device or a printout of their medication to the hospital. It might be essential, but difficult, to remember who prescribed the medication when you want a renewal: ‘With some you know and with some you do not know’ (P4). One participant would ‘start thinking: is it for my heart? Or is it for something else? And that is the way you find out’.

Moreover, the participants noted that side effects of medication sometimes interfered with daily life. Two participants mentioned that after they take their morning medication they ‘do not feel well’ and have to ‘take it easy for a few hours’ or ‘take a nap’. One participant reported how a side effect caused an acute hospitalisation. The participants also described different coping strategies: one participant described that he ‘will just stop with that medicine’, sometimes without discussing this with the doctor, where another described always contacting the doctor for advice when experiencing side effects.

b) Managing multiple appointments

Multiple appointments are indispensable

In general, visiting the hospital was considered a necessary evil when living with MCC. The participants described that they gradually become experienced in planning and logistics and that multiple appointments ‘are a part of it’ and ‘have to happen’. Two participants remarked that it takes a lot of time, because each doctor only focuses on his own specialty. On the other hand, some participants mentioned the comfort ‘when the keep an eye on you’; they did not think it is a burden. Hospital visits usually offered reassurance and contentment when everything was stable and clear, but when elements remained unclear or uncertain they could cause several negative emotions, according to the participants. Overall, they considered multiple appointments to be indispensable.

Combining appointments: desired by most, but only occasionally possible

Logistically, it required planning and initiative for most of the participants to manage and coordinate the multiple appointments. One participant never asked for a combination, so ‘it never happened’. Two participants described how they inquired about the possibilities, but with little success: ‘the other doctor had no available appointments’ (P4) or ‘We cannot plan this appointment half a year in advance, you will receive a letter at home. I have tried calling, but by then he is completely booked, and nothing can be moved.’ (P5’s family member) However, two other participants had inquired for a combination with more success and three participants noted that they sometimes find a ‘smart’ assistant who notices the other appointment and offers to combine them.

Seven out of eight participants reported that they would prefer combining appointments. They said: ‘it would be pleasant to handle everything on one day’. One participant mentioned: ‘It is of little importance for me. I am retired and I live close to the hospital.’ (P7)

More dependency or symptoms required more planning

Physically going to several appointments required organisation and time, effort and was costly (especially parking costs), according to the participants. They might have to make an appeal to their friends or family repeatedly or take time-consuming public transportation to get to the hospital. Moreover, sometimes it was necessary to bring a companion such as one of their children, their partner or a, sometimes paid, family friend. Some depended on their companions for transportation; others took companions for support or an extra ear to ‘listen in’ in the consultation room, especially when ‘there are new things’.

For some participants, this dependency on others resulted in feelings of guilt for taking up their time: ‘I find it much worse for (P5) They described how they try to adapt the appointments to their companions’ schedules. This was one of the main reasons why two participants who did not mind going to the hospital regularly, still preferred the combination of appointments.

c) Doctor-doctor communication

Participants usually assumed that doctors will consult each other if necessary and that they can read about new developments in their electronic file. All participants thought that interdisciplinary consultation would be beneficial. They reckoned it would help doctors to ‘be informed about their patients’ and ‘take each other into consideration’. Two participants thought it would benefit the speed of the (diagnostic) process.

However, the participants said that they do not see or hear doctors communicating about them. Ideas about doctor-doctor communication varied from ‘No, I do not think there is any communication’ to ‘I suppose there is communication, because somehow they know what to take into account’. Three participants described situations where they found themselves in-between two doctors who said different things about the proposed treatment, either within the hospital or when consulting doctors in two different hospitals.

The participants reckoned that all information about them and their conditions could be found in their electronic file on the computer, if necessary: ‘they can see all information [in the computer], if they want to’. The participants described that some doctors take the initiative to check if anything new has happened. One of the participants mentioned that the doctor often ‘first starts the computer’ and ‘gazes towards the screen’. Some participants described that they take the initiative in pointing out to the doctor that they have ‘visited their colleague’, ‘something has changed’ or ‘another doctor has blood results’.

d) Being an experienced patient

Experience provides strategies to survive in the hospital

Participants illustrated the knowledge they had acquired after regularly visiting the hospital. They described how they know for each outpatient clinic and doctor how much time to calculate for waiting and for the appointment. The experiences within one hospital, but also in different or former hospitals, offer grounds for comparison: ‘Over there, you could read everything in your own medical file.’ (P7) Although they ‘know their way around the hospital’, the participants still experienced barriers in getting what they want or need. Participants described how they use strategies such as ‘send a child/partner’, ‘get emotional’ or ‘repetitively request something’. 'It was an unintended result of encountering a barrier or used on purpose. Participants said they ‘regret’ that they have to use these strategies, but described that ‘this is how it goes’ sometimes.‘ Yes, that too is experience. It is not a good thing, it is a pity it is the way it is, you against the struggles of a hospital. But anyway, experience delivers at a certain point. (…) You are not impressed by a white coat anymore.’ (P4’s family member) Most of the participants also mentioned they see that many healthcare professionals suffer from a high work-pressure. They described that is why they are usually ‘understanding’ when there are waiting times, few available appointments or scarce communication between doctors.

Communication, feelings and expectations in the hospital

Although the following themes are presumably not unique for a patient with MCC, they seemed important enough for the care experience to mention. The participants mentioned that some things that are connected to the treatment by healthcare professionals in the hospital are out of their control. These were recurrent or incidental events they simply ‘have to accept’ or ‘undergo’, such as waiting times, the occurrence of complications and hospitalisations. The participants described the importance or lack of communication and the evoked feelings and expectations for these events.

e) Content of appointments

Every appointment comes with its own feelings and expectations

During analysis of the interview sections about the multiple appointments in the hospital, it struck the researchers that different types of appointments gave rise to different feelings and expectations according to the participants. Not all participants specifically mentioned different feelings and expectations, but what they did mention is summarised in table 3.

f) Doctor-patient communication

All participants described several experiences with the communication by healthcare professionals. There was always an event or specific type of behaviour that evoked feelings with certain consequences, according to the participants. ‘Proper’ consultations seemed to be a result of an optimal combination of content and behaviour of a healthcare professional. Participants described a clear-cut and relaxed consultation with a professional who ‘listens and takes time’, ‘is interested and understanding’ and who ‘treats them like a human’. The participants also described ‘bad’ consultations, where healthcare professionals did the opposite of one or more of the above mentioned. They depicted healthcare professionals who did not seem to listen or be interested because ‘they were completely focused on the computer screen’ or ‘they nearly broke their neck to get to the coffee table’ after a short consultation.

g) Errors, complications and oddities

Insufficient communication might result in dissatisfaction

Six out of eight participants described that they experienced an error or complication in the past. Sometimes without permanent repercussions, but other times with outcomes that influence the quality of their lives. Whether the participants reported on a ‘big’ event, such as an error or complication, or on an oddity, the discontent always seemed to be caused by an experienced lack of or insufficient communication.

‘So maybe I also felt like the doctors were ashamed too. But I thought: you should have thought it through. I do hope someone said something internally, like ‘boys, this has to go differently from now on’. But I do not know whether that happened.’ (P7)

h) Communication from and to the hospital

Climbing the wall to reach the hospital doctor

When they have a question about a treatment plan or medicine, most participants said they (would) ‘try to contact the hospital doctor’. Some of the participants never tried to contact their hospital doctor and one participant mentioned he did not know whether he would try if he had a question. Two participants described their experiences: ‘you will first get the assistant, you have to ask your question and then the assistant will discuss this for you’. One participant was content about this, but one family member was less satisfied: ‘Sometimes because of the answer to the question, you have more questions, but the assistant cannot give you the answer. This can become a time-consuming process.’ (P4’s family member) Overall, most participants experienced a wall to reach their own hospital doctor: they thought or experienced that ‘assistants are instructed to keep everything away’. This often resulted in dissatisfaction or in refraining from calling the hospital doctor, the participants reported.

DISCUSSION

Relationship to existing literature

In a qualitative study on the management of MCC in the Canadian community setting, the participants described their struggle with loss of functional ability and the gradual decline, which are similar to the struggles of our study populatio19 This decline seemed to result in ambivalent coping: the participants were sometimes forced to acknowledge their healthcare needs, while on the other hand they did not always want to focus on ‘being ill’. According to previous research, physical functioning and quality of life are associated with MCC. Increasing age is also a contributing factor: it is related to more MCC and physical functioning.10-21 Moreover, a review by Ryan et al. indicated that the number of conditions and disease severity were predictors of functional decline.22 This study emphasises the significant roles that gradual and functional decline play in a patient’s life with MCC.

Our study also indicates that keeping an overview of diseases, appointments and health professionals in the hospital can cost initiative, attention and effort. The ability to keep an overview and the need for information might be influenced by individual characteristics. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the need for information depends on a patient’s characteristics, including education, skills, coping strategies, preferences and beliefs.23 From a health and social perspective, patients can be distributed on a sliding scale (figure 1).24

The patients who were interviewed for this study might be outspoken participants because of the selection procedure. Moreover, as mentioned before, they were relatively independent, cognitively strong and/or supported by family, so they were most likely positioned somewhere in the middle of this scale. For patients positioned on the outer left side it might require even more effort to keep an overview or not even be possible. However, on the outer right side, patients might experience few difficulties. Therefore, our participants’ abilities and needs, but also the required effort to keep an overview might differ from individuals with other characteristics or positions on this scale.

Moreover, MCC and its complexity do not seem to fit into the current care design. The Canadian community study concluded that the health and social care systems do not have the ability to meet the needs of older adults and caregivers and the participants experienced fragmentation of care.19 Our participants reported the same fragmentation in their secondary care experience: multiple appointments that were rarely combined, possibly conceivable communication between their hospital doctors and multiple medicines from different prescribers. Overall, the complexity of MCC seems to be a barrier to optimising care, but also to the patients’ and doctors’ knowledge about the different diseases, treatments and interactions.13

‘Experienced difficulties in interacting with the healthcare system’ are defined as ‘hassles’.11,25 Our participants described how many of processes and logistics in the hospital’s outpatient clinic remain unclear, but they have assumptions about them. They reported that because of the multiple visits and observations they make, they became experienced and developed strategies to manage their own cases within the hospital and cope with these hassles. Two other studies described that patients with MCC reported experiencing more ‘hassles’ than patients with a single condition. These hassles usually concerned the amount of information about their diseases, taking medication, finding time or the right moment to discuss all of their problems or poor doctor-doctor communication.25-27 Moreover, Kenning et al. reported that these ‘hassles’ were predictors for self-management in patients with MCC.11

Consequently, hassles appear to play an influential role in patients’ secondary care experiences and in patients self-management, in the hospital and at home.

Communication seems to have a crucial influence on expectations and feelings and presumably affects the secondary care experience for patients with MCC as well. Our study provides a modest insight into how experiencing different communication styles and multiple different appointments with several healthcare professionals resulted in various expectations and feelings. Moreover, our study offers a personal insight into the specific feelings that were elicited by either good or poor communication. The Institute for Healthcare Communication emphasises the importance of good communication between healthcare professionals and patients. Their research shows that for all patients, communication seems to play a large role in patient satisfaction and experience, but also in adherence to treatments, self-management and prevention behaviour.28 According to a recent randomised controlled trial, being empathetic and inducing positive expectations has a significant effect on reducing anxiety and negative mood and increases satisfaction.29

Overall, the study findings indicated that the planning, logistics and communication of being a patient with MCC in the hospital demands considerable effort from this specific group of patients. However, the needs and abilities for organisation and overview might differ, based on individual factors. Partly because of experiencing hassles, the participants seemed to have gradually become experienced patients. Concurrently, the quality of communication might be an important influence not only on patients’ experience, but also on the patients’ management of themselves.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Strengths

The participants suffered from many comorbidities, had experiences with multiple hospital doctors and most of them had visited the outpatient clinics very often in the last year, which made them ideal patients to share their experiences for this study. The interviews were mostly done at the participant’s home, in a trusted environment and were conducted by an independent interviewer who had no apparent relation with any of the healthcare professionals in the hospital. If the interviewer sensed a certain level of reservation in patients to openly express their feelings, the interviewer actively assured them that the interviews would be processed anonymously and that the information they provided would by no means be transferred to the healthcare provider in a way that could unravel their identity. The semi-structured design offered an insight into the expectations, feelings and coping strategies these patients have and developed.

Limitations

Data saturation was achieved after including only eight patients. There was variation in age and education, with a small overrepresentation of patients aged 65-74 years and 50% low education level against 19% in the general population aged 65 years and above in the Netherlands in 2014.30 Moreover, all participants were Dutch and relatively independent. So this seemed to be a relatively outspoken and fit population without much cultural diversity. However, as patients with multiple chronic conditions are often older with a lower education level, the variation in age and education was expected for this sample.

Nevertheless, younger patients, patients with a different ethnicity or more dependent patients might not endorse the results. Changing the selection procedure to include more diverse patients might lead to different results.

Implications for the future

he complexity of MCC might require a more coordinated, individualised approach of care, as the World Health Organisation (WHO), the American Geriatric Society(AGS) and the NICE guideline described.13,31,32 However, an overview of the patient’s conditions, care providers and treatments seems an essential element for this approach. In our research, the relatively independent and cognitively strong participants and their family members described that the organisation of the conditions and appointments could require a great effort. Despite their efforts, the course of events could remain obscure and the logistics within the hospital non-transparent. At the same time, healthcare professionals seemed to operate only on their separate islands. If policymakers think a coordinated and individualised approach is beneficial for patients with MCC, we might first have to answer the question: whose responsibility is it to create and maintain an overview of the care for a patient with MCC?

However, not every patient might require and desire more coordination and communication regarding their care. Organising multiple appointments and doctor-doctor communication are themes that seem specifically related to MCC and improving these aspects might improve the care experience for patients with MCC. However, it might be necessary to narrow the target group for these interventions first, as not all participants in this study felt the same desire for change as others. On the other hand, information or feeling sufficiently informed about diseases, treatments or logistics seems to be one of the pillars for a good patient experience, according to our participants, but also to other studies on care experience of patients with MCC.25-27 The participants seemed to fill their gaps of information with assumptions and eventually with experience. They all report the need for information, but to what extent differs. More coordination and communication might particularly be required by patients who are dependent, who do not have support from their environment or suffer from (mild) cognitive disorders.33

In conclusion, future research could focus on finding ways to create overview and defining responsibilities of the care for patients with multiple chronic conditions. Moreover, it could attempt to clarify which group of patients needs assistance and how to improve communication and care coordination for them. Overall, patients’ care experience could play an important role in implementing a coordinated, individualised approach of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions.

DISCLOSURES

All authors declare no conflict of interest. No funding or financial support was received.

REFERENCES